Improve your VO₂ max

Choosing training methods that match your fitness level and ability to recover.

Updated Feb 2026Recent research identifies VO₂ max as a leading indicator of survival and cardiovascular health. Studies show that the higher your score, the lower your health risk, even for people who are already in good shape (1-2).

If you want to improve your VO₂ max, you need workouts that are demanding enough to stimulate adaptations in your muscle cells, heart, blood vessels, and lungs. But which workouts will make you fit without taking too much time or increasing your risk of injury?

The answer depends on your current fitness level.

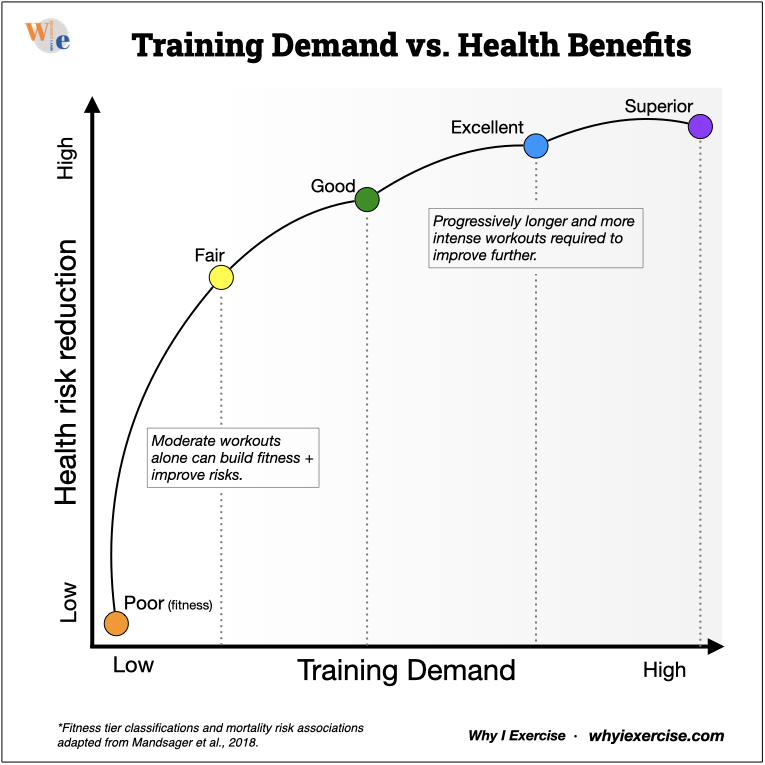

How Training Demands Change as Fitness Increases

Training demands rise as you approach your physiological ceiling. Early gains come from moderate, consistent effort. As fitness improves, further progress requires more time, progressively harder training, and higher-quality recovery.

VO₂ max fitness tiers showing how training demand increases while health risk reduction begins to plateau.

VO₂ max fitness tiers showing how training demand increases while health risk reduction begins to plateau.Early Progress (Poor → Fair)

Training at this fitness level delivers the largest health return per hour invested. Risk drops quickly, and everyday activities feel noticeably easier within months.

Consistency drives your progress. Focus on building a sustainable habit. Almost any structured aerobic activity—walking, aerobic classes, or recreational sports—can improve fitness when repeated regularly at a moderate effort.

Mid-Level Progress (Fair → Good)

Improvement beyond average offers greater health protection and better physical performance, though the return for your training effort is not as dramatic as the initial jump.

Further gains require longer steady aerobic sessions and periodic vigorous intervals, with consistent weekly frequency.

Advanced Progress (Good → Excellent → Superior)

Increasing your fitness at this level is a buffer against age-related decline. Gains also provide small additional improvements in mortality risk.

A higher VO₂ max extends your active longevity. It delays the point where aging drops your capacity below the level needed for your preferred sports and active hobbies.

Advancing further requires work closer to your upper aerobic limits, like repeated threshold or high-intensity intervals, carefully spaced to allow for recovery between demanding sessions.

Maintenance (Any Tier)

Fitness decays without enough training stimulus, eroding health protection and functional capacity over time.

Exercise intensity is key for maintaining endurance performance. Maintain your previous effort level on roughly half your improvement workload, and you can reduce training volume and frequency for months at a time (13).

For all levels

Track training effectiveness: Retest quarterly with the same field test (Rockport or Cooper). If your score holds within 5%, your approach is working. For reliable monitoring between tests, the 3-Minute Step Test can provide quick aerobic checks every few weeks.

How to Choose Workouts to Improve Your VO₂ Max

Moderate training, intervals, and sprint work all contribute to fitness development. Research shows each method is effective for improving VO₂ max (6, 9, 10). But the most sustainable progress comes from matching training methods to your fitness level and your available recovery.

The less experienced and fit you are, the smarter it is to limit your intensity, as overtraining and injury can halt your progress for weeks or even longer. Building consistent moderate-intensity volume allows for a safer progression before adding harder sessions.

As you develop your fitness, you'll benefit from pairing moderate training with higher-intensity sessions. You may have heard about high-intensity interval training (HIIT) as an efficient way to improve VO₂ max.

HIIT is effective, but it represents just one category of higher-intensity work. The sections below describe the full range of methods—from moderate training to longer intervals and sprint efforts—and how each fits into a sustainable approach.

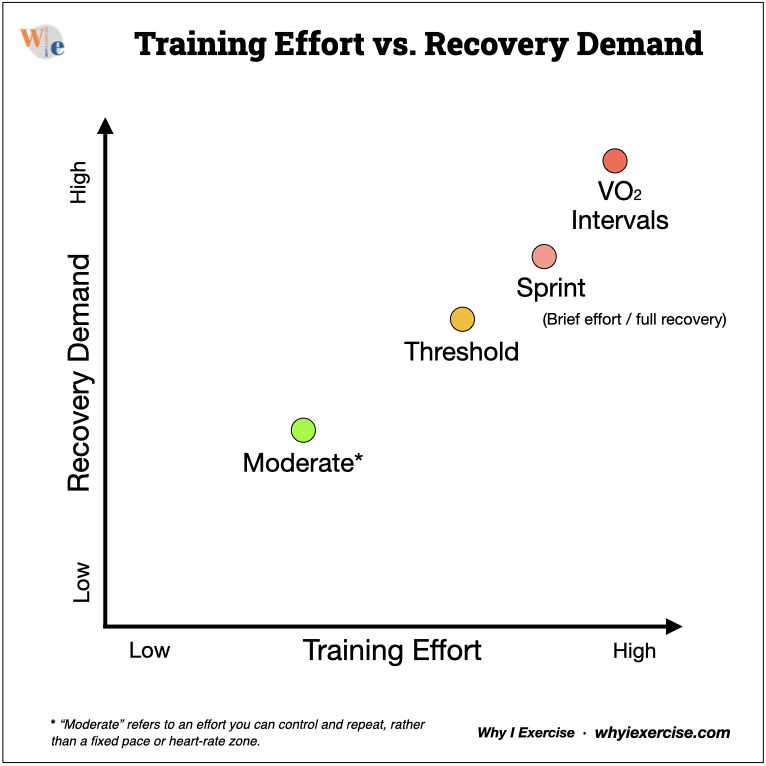

Training Method Quick Reference

Use this guide to understand training intensities. How often you include each method depends on how easily you recover from sessions and on your training readiness, covered in the weekly scheduling section below.

Higher-intensity sessions require proportionally greater recovery, limiting how often they can be repeated. Recovery demand varies with session volume and individual capacity.

Higher-intensity sessions require proportionally greater recovery, limiting how often they can be repeated. Recovery demand varies with session volume and individual capacity.| Method | Effort (RPE) | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate | RPE 3–4/10 | Beginners, sustainable training, lower injury risk |

| Threshold | RPE 6–7/10 | Consistent challenging work, long-term development, lower recovery demand |

| VO₂ Intervals | RPE 8–9/10 | Moderate or greater fitness level, breaking plateaus, race/competition prep |

| Sprints | RPE 9+/10* | High muscle and tendon load, requires learning techniques and gradual adaptation |

*Peak rep intensity is 9+, but full recovery between efforts makes overall session demand lower than sustained VO₂ max intervals.

RPE (Rating of Perceived Exertion) Effort Level Guide:

- RPE 3–4: Can speak comfortably in full sentences (~60–70% max HR)

- RPE 6–7: Short phrases; effort is controlled but demanding (~80–85% max HR)

- RPE 8–9: Few words between breaths; effort sustained for minutes (~90% max HR)

- RPE 9+: Very Intense, out of breath (near-max; heart rate often lags the effort). Normally used in brief interval reps, paired with full recovery between reps,

Recovery matters more than frequency. Research often uses multiple high-intensity sessions per week to demonstrate measurable adaptations. But most people, including top endurance athletes, make better long-term progress by emphasizing adequate recovery between intense workouts, rather than pushing for frequent hard efforts.

How often to include higher-intensity sessions, and when to pull back, is where readiness and recovery become critical. That decision depends more on the individual than the method itself.

Improve your VO₂ max with moderate intensity training

Moderate training sessions are performed at a steady, sustainable effort with controlled breathing. Training at this level is often referred to as as "Zone 2", with heart rate typically around 60–70% of maximum. It's easy enough for you to speak in short sentences without strain.

Depending on your fitness level, a moderate-intensity workout that can support VO₂ max improvement may include a 30–50 minute steady-paced brisk walk, bike ride, or jog. Research protocols using consistent moderate training have demonstrated VO₂ max improvements around 10% over 8-12 weeks (6).

If you haven’t been exercising at all, start with 10-12 minutes of steady-state exercise per day. This is enough to give you health benefits while you build up to the 30-minute plus level that is proven to increase your VO2 max (12). Increase by 10% per week or less so your body has time to get used to the training.

Moderate-intensity training supports long-term progress by making it easier to train again the following day. You should finish sessions with energy in reserve, which allows consistent repetition over time.

As fitness improves, moderate training can progress into vigorous intensity (RPE 5–6). Breathing is noticeably deeper but remains controlled. Sustained conversation becomes more difficult.

Example workouts include sustained faster-tempo efforts or controlled pace changes within an otherwise steady session. These efforts are less intense than structured interval work.

Vigorous sessions provide a stronger stimulus than steady moderate work while remaining repeatable. For mid-level progression (Fair → Good), this training intensity helps drive continued progress without the higher recovery demands of threshold or high-intensity intervals.

Moderate and vigorous training form a durable aerobic foundation, preparing you for more demanding workouts when appropriate.

Improve your VO₂ max with long interval training

Long-duration interval training sessions are highly demanding, requiring very hard efforts sustained for several minutes at a time.

During each interval, you can usually speak only a few words between breaths, especially toward the end of the effort, as heart rate reaches about 90% of maximum. These workouts, also known as VO2 max intervals, challenge your ability to tolerate discomfort.

An example interval workout might include four-minute bursts of faster effort, with three-minute easy recoveries between each bout to allow breathing and energy to rebound.

Workouts using four reps of these four-minute intervals have been studied for their effectiveness in VO2 max training (8, 9), but in practice, endurance athletes use many variations of these intervals depending on their sport and race distance. Examples from running include six half-mile runs or three one-mile runs at a hard effort with about 1/2 or more of the running time to recover between each rep.

For most people, the training value of VO₂-max-interval sessions comes from how well the workout is executed. The difficulty and intensity of these sessions make it easy to miss the intended effort without preparation or guidance. When workouts start too fast, lose quality, or are repeated too often, their effectiveness declines and recovery becomes more difficult.

This type of training is most commonly used by competitive athletes at specific points in their training cycle as they prepare for competition. Endurance athletes typically build both fitness and recovery capacity to get the most benefit from such demanding sessions.

Threshold Intervals

Long-interval workouts can also be performed at slightly lower intensities, referred to as threshold training. These sessions use similar or longer interval durations (3–10+ minutes) with an effort marked by strong but controlled breathing (RPE 6-7/10). As a whole, these sessions are more sustainable and easier to execute than VO2-max interval training.

Threshold is widely used in endurance training programs, aimed at building durable fitness over time. It does not reach the same peak stimulus as VO₂-max intervals, but it is less demanding and easier to recover from, making it more repeatable across weeks of training.

Improve your VO₂ max with sprint workouts

Sprint workouts involve brief, near-maximal efforts separated by longer rest periods that allow full recovery before the next repetition. Breathing becomes very intense immediately after each sprint, then settles back toward baseline before the next effort. This pattern distinguishes sprint training from sustained interval sessions.

A simple example might include six 30-second running or cycling sprints, with two to four minutes of easy recovery between efforts to restore breathing and energy.

HIIT vs. Sprint Training: Key Differences for VO₂ Max Training

These workouts are often grouped together, but they have distinct training demands and produce different adaptations.

| Feature | HIIT | Sprint Training |

|---|---|---|

| Effort | Very hard, submaximal | Near-maximal |

| Recovery | Brief or incomplete | Full recovery between reps |

| Primary Stress | Cardiovascular + metabolic fatigue | Neuromuscular power and speed |

| Typical Structure | Repeated short intervals | Brief maximal efforts |

| Best Use | Occasional stimulus or short blocks | Specific power and speed development |

Both HIIT and sprint training can improve your VO₂ max when applied well. Their differences in rest periods, effort, and focus affect how tiring they feel and how long you can keep them up. In practice, HIIT is often used for short, focused phases, while sprint work is more commonly blended into longer-term training with attention to recovery.

In this article, HIIT refers to cardio-focused interval training; many group or “HIIT” classes combine cardio and strength, which creates a different training stimulus.

In my sprint interval sessions, I incorporate cross training by pulling a lightweight sled uphill for several of the reps.

In my sprint interval sessions, I incorporate cross training by pulling a lightweight sled uphill for several of the reps.Because sprint efforts are powerful and fast, training modes that limit speed can help preserve technique. Uphill running, increased resistance on cardio machines, sled work, or soft surfaces like grass and sand can all reduce joint stress while maintaining high effort. The goal is to produce maximal effort without sacrificing control.

Sprint training places high demands on muscles and connective tissue, so a thorough warm-up is essential. Dynamic stretches, calisthenics, and movement drills that gradually increase intensity help prepare the body for maximal efforts and reduce risk of strain.

Studies using sprint interval training have reported VO₂ max improvements of roughly 7–10%, depending on baseline fitness. A meta-analysis also found that less-fit participants achieved meaningful gains using a small number of sprint repetitions per session (10, 11). These studies highlight sprint training as a potent stimulus to boost capacity in a brief training period.

Because sprint sessions are demanding, their long-term value depends on recovery and repeatability. When balanced appropriately with lower-intensity training, sprint work can contribute to aerobic development while preserving the ability to train consistently over time.

See demonstrations of the workouts from this article in this YouTube video from Why I Exercise.

Creating a Weekly Schedule to Improve Your VO₂ Max

Improving VO₂ max doesn’t require daily hard workouts. Training weeks averaging three sessions that meaningfully challenge your aerobic system are often enough to drive progress, especially when those sessions are repeatable.

Those sessions don’t have to be identical, traditional cardio workouts. The most sustainable way to boost VO₂ max long-term is blending activities you enjoy with targeted cardio work—motivation drives consistency more than perfect session matching.

Sports, recreational activities, and non-traditional cardio can all contribute, and how often each of the activities appear in a given week depends less on the calendar and more on how quickly you recover from them.

Frequently asked Questions

1. How long does it take to increase VO₂ max?

Meaningful improvements can occur within 8–12 weeks, especially if you're starting from a lower fitness level. Changes of this size are often enough to reduce health risk and make workouts feel noticeably easier. If you're already moderately fit, improvements tend to be smaller and may require longer, more targeted training to accumulate.

2. What type of training improves VO₂ max the most?

Multiple training methods can improve VO₂ max, including moderate-intensity training, threshold work, long intervals, and sprint training. The most effective approach depends less on a single method and more on matching training to your fitness level and recovery capacity. Early progress benefits from moderate consistency; mid-level fitness responds to vigorous efforts; advanced improvement requires structured intensity. Mixing methods based on your current tier produces better long-term results than exclusive focus on one approach.

3. Do VO₂ max improvements plateau?

Yes. The demand curve earlier in this article shows this pattern: improvement slows as you approach your physiological ceiling. Early gains occur with moderate stimulus; later gains require stronger, more structured training and higher-quality recovery. If progress has stalled despite consistent training for 3-6 months, review your training structure, intensity progression, and recovery patterns.

4. Is Zone 2 or moderate training enough to improve VO₂ max?

Zone 2 and moderate training improve VO₂ max effectively for people with low or average fitness. As fitness increases, Zone 2 remains valuable for building volume and supporting recovery, while higher-intensity sessions like threshold or interval work become more important for continued VO₂ max gains.

5. How are threshold workouts different from VO₂ max intervals?

Threshold workouts use similar or longer interval durations but at a slightly lower, more sustainable intensity. Breathing is strong but controlled, and recovery between sessions is easier. This makes threshold training more repeatable across weeks, even though it doesn't reach the same peak intensity as VO₂-max-oriented intervals.

6. How much exercise per week is needed to improve VO₂ max?

There isn't a single weekly formula that works for everyone. Research protocols often use 3-4 sessions per week to demonstrate adaptations, but your optimal frequency depends on recovery capacity, training history, and other life demands. Starting with 3 training sessions per week allows you to build consistency while leaving room to add intensity as recovery permits. Training you can repeat week after week produces better long-term results than pushing unsustainable frequencies.

7. Can I maintain VO₂ max with less training?

Yes. You can maintain endurance performance for extended periods with less training. Maintain the intensity of your key harder sessions and you can reduce your weekly training time by about half without loss of fitness. Retest quarterly - if your score holds within 5%, your reduced training is working.

8. How often should I retest VO₂ max?

Retest every 8-12 weeks during improvement phases to track progress and verify training effectiveness. During maintenance, quarterly retesting is sufficient - if your score holds within 5%, your approach is working. Testing too frequently can amplify normal variation. Use the same protocol each time. The Rockport Walking Test and Cooper Test provide consistent benchmarks, while the 3-Minute Step Test offers lighter interim checks.

9. How accurate is my smartwatch VO₂ max estimate?

Smartwatch VO₂ max estimates can be useful for tracking trends, but individual readings often vary due to algorithm assumptions and measurement error. Field tests like the Rockport or Cooper protocols provide more consistent benchmarks for tracking change over time.

10. Is it worth improving VO₂ max if I'm already in the Good range?

By the Good tier, you've captured most of the available health risk reduction. Further gains shift from health necessity to active longevity: a higher baseline delays age-related decline (~10% per decade), extending the years you can maintain preferred activities and functional independence. At this level, improving VO₂ max becomes a personal choice driven by enjoyment and long-term capacity goals, not health urgency.

11. Can you improve VO₂ max at any age?

Yes. VO₂ max typically declines with age, but regular training can slow that decline and improve functional capacity at nearly any age. Improvements may be smaller or slower later in life, but they remain meaningful for health and performance.

About the author

Rob Cowell, PT, the founder of Why I Exercise (est. 2009), is a physical therapist with 29 years of clinical experience. He specializes in evidence-based fitness, movement coaching, and long-term conditioning, and he maintains high personal fitness through running, calisthenics, and beach volleyball.

References

1) Mandsager K, Harb S, Cremer P, Phelan D, Nissen SE, Jaber W. Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness With Long-term Mortality Among Adults Undergoing Exercise Treadmill Testing. JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Oct 5;1(6):e183605. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3605. PMID: 30646252; PMCID: PMC6324439.

2) Kokkinos P, Faselis C, et al, Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Mortality Risk Across the Spectra of Age, Race, and Sex. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Aug 9;80(6):598-609. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.05.031. PMID: 35926933.

3) Kent, M. The Oxford Dictionary of Sports Science and Medicine, 3rd Ed., Oxford Univ. Press, 2007

4) Caselli S, Di Pietro R, Di Paolo FM, Pisicchio C, di Giacinto B, Guerra E, Culasso F, Pelliccia A. Left ventricular systolic performance is improved in elite athletes. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011 Jul;12(7):514-9. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer071. Epub 2011 Jun 8. PMID: 21653598.

5) Joyner MJ, Casey DP. Regulation of increased blood flow (hyperemia) to muscles during exercise: a hierarchy of competing physiological needs. Physiol Rev. 2015 Apr;95(2):549-601. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2013. PMID: 25834232; PMCID: PMC4551211.

6) Scribbans TD, Vecsey S, Hankinson PB, Foster WS, Gurd BJ. The Effect of Training Intensity on VO2max in Young Healthy Adults: A Meta-Regression and Meta-Analysis. Int J Exerc Sci. 2016 Apr 1;9(2):230-247. PMID: 27182424; PMCID: PMC4836566.

7) Gabbett TJ. The training-injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? Br J Sports Med. 2016 Mar;50(5):273-80. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788. Epub 2016 Jan 12. PMID: 26758673; PMCID: PMC4789704.

8) Støren Ø, Helgerud J, Sæbø M, Støa EM, Bratland-Sanda S, Unhjem RJ, Hoff J, Wang E. The Effect of Age on the V˙O2max Response to High-Intensity Interval Training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017 Jan;49(1):78-85. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001070. PMID: 27501361.

9) Bacon AP, Carter RE, Ogle EA, Joyner MJ. VO2max trainability and high intensity interval training in humans: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013 Sep 16;8(9):e73182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073182. PMID: 24066036; PMCID: PMC3774727.

10) Vollaard NBJ, Metcalfe RS, Williams S. Effect of Number of Sprints in an SIT Session on Change in VO2max: A Meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017 Jun;49(6):1147-1156. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001204. PMID: 28079707.

11) Weston M, Taylor KL, Batterham AM, Hopkins WG. Effects of low-volume high-intensity interval training (HIT) on fitness in adults: a meta-analysis of controlled and non-controlled trials. Sports Med. 2014 Jul;44(7):1005-17. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0180-z. PMID: 24743927; PMCID: PMC4072920.

12) Garcia L, Pearce M, et al. Non-occupational physical activity and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and mortality outcomes: a dose-response meta-analysis of large prospective studies. Br J Sports Med. 2023 Feb 28:bjsports-2022-105669. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2022-105669. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36854652.

13) Spiering, Barry A., et al. Maintaining Physical Performance: The Minimal Dose of Exercise Needed to Preserve Endurance and Strength Over Time. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 35(5):p 1449-1458, May 2021. | DOI: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003964