Low VO2 max

How to overcome poor cardio fitness.

If you've had trouble improving your low VO2 max and you don’t feel naturally inclined toward endurance exercise, there may be several factors affecting your struggle with cardio conditioning.

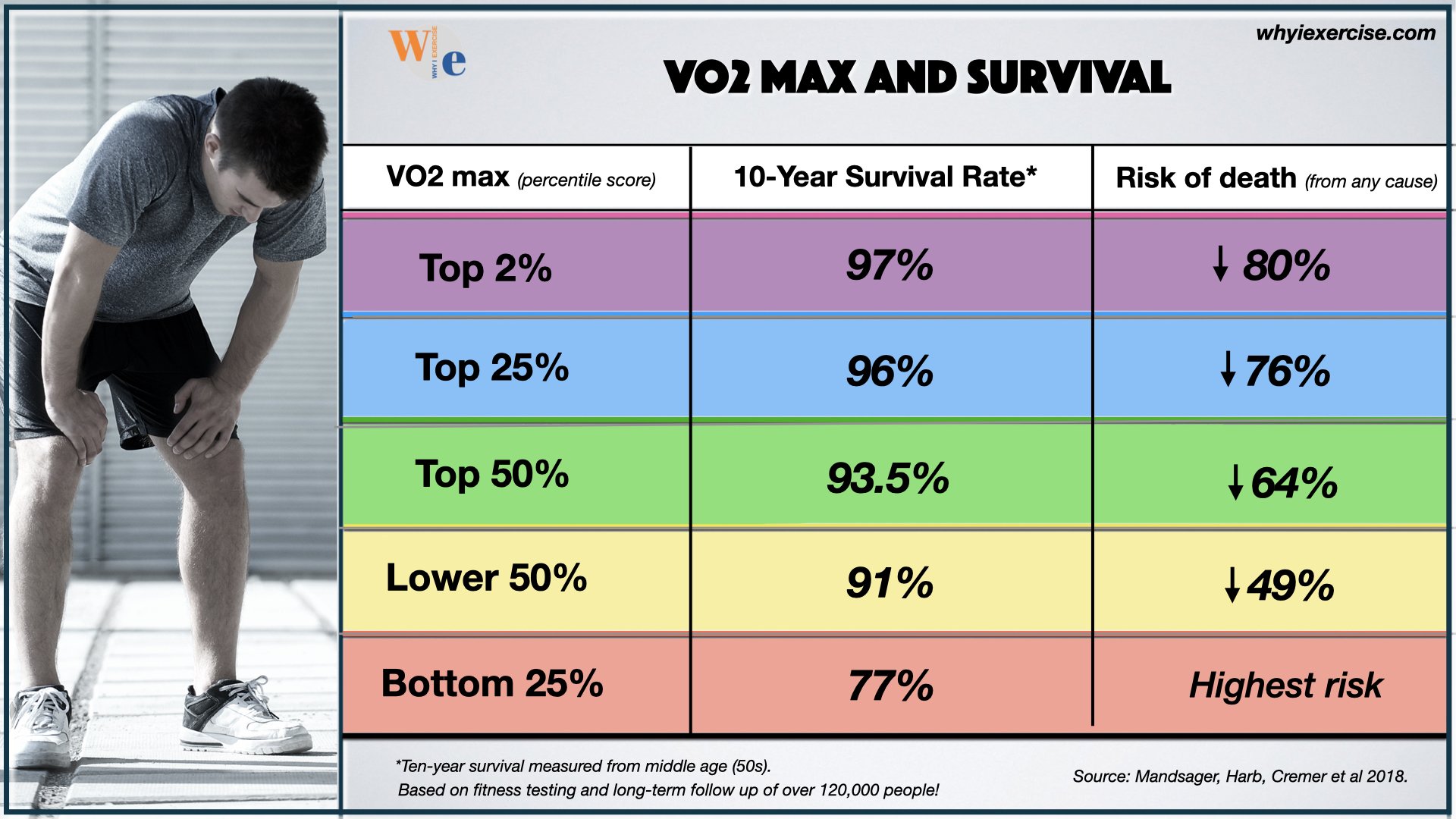

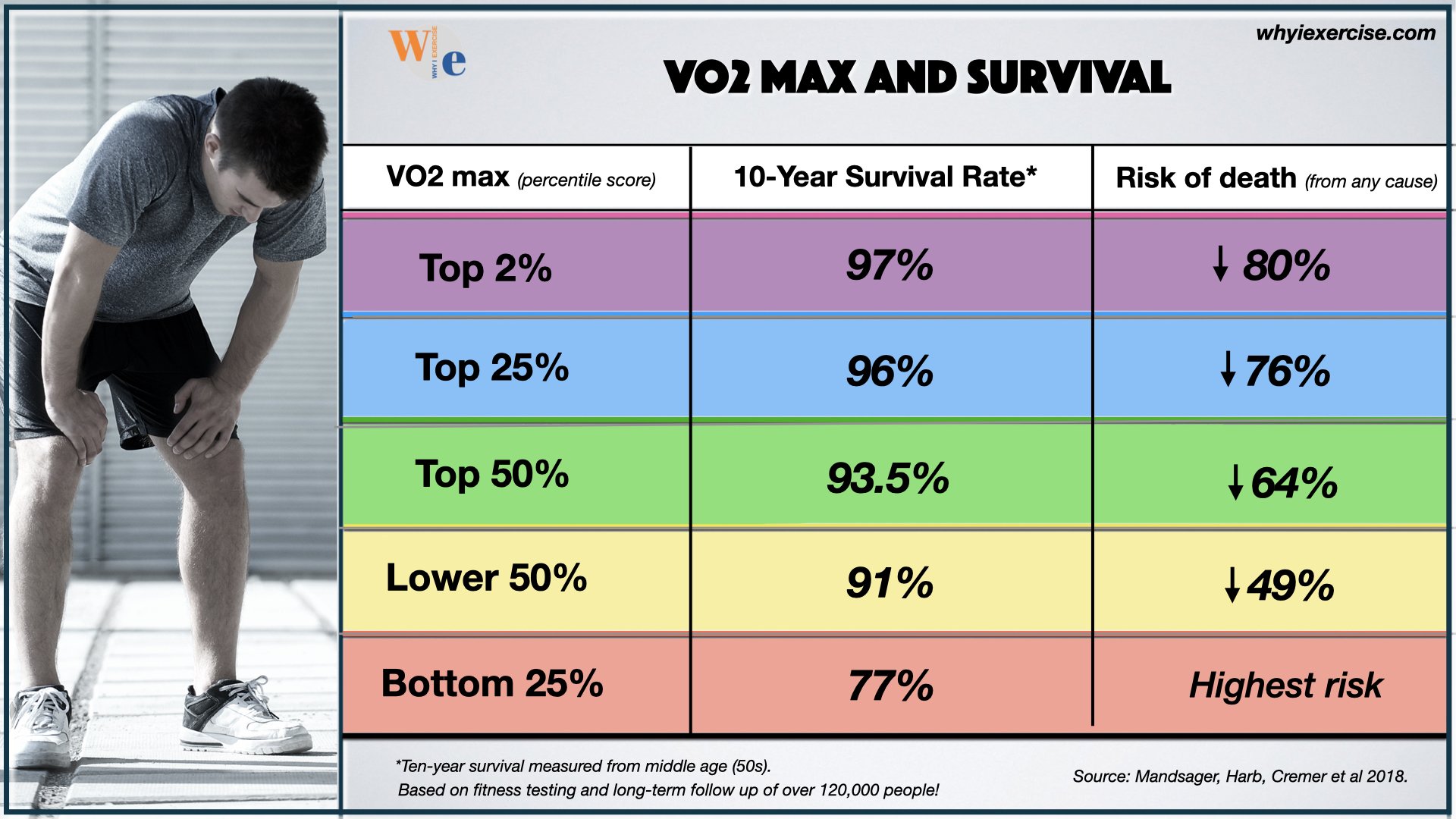

Body mass index, body fat distribution, aging, nutrition, sleep quality, stress, and genetics can all affect your ability to exercise and improve from training. Low VO2 max is proven to affect our survival rate and risk of death, which makes these seven factors worth examining further.

Low VO2 max, body weight and body fat distribution

42% of US adults are currently obese (BMI > 30), and studies show that VO2 max trends higher for those with a lower body mass index and a smaller waist circumference (1-2). Hurdles to becoming fitter include a higher likelihood of arthritis and chronic pain at BMI > 30 compared to lighter-weight peers (3-4).

Despite the challenges, an increasing number of obese people are finding ways to maintain good cardio fitness. A 2018 review of studies found that people who are obese and fit have a lower mortality risk than normal-weight peers who are out-of-shape (5).

Good fitness is possible at all sizes, but fitness becomes harder to maintain for those with a 30+ BMI.

Good fitness is possible at all sizes, but fitness becomes harder to maintain for those with a 30+ BMI.According to numerous studies, VO2 max is more important than BMI for preventing all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (1, 5-6). Higher fitness in people with a BMI > 30 is associated with metabolic health indicators, such as normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar (7).

Maintaining a strong VO2 max at a high body weight is an impressive achievement, shown to be highly beneficial for your long-term health. But it may be easier said than done, particularly for those with a high waist circumference (6).

People with a BMI below 30 are significantly more likely to maintain good cardio fitness for the long term than those above 30. For more info, visit our body mass index article, part of a guided self-assessment that allows you to calculate your BMI, factor in your waist and hip measurements, and compare your scores to optimal standards for low health risks.

Low VO2 max and aging

VO2 max is proven to decline with aging, yet people of all ages have been able to improve their scores.

VO2 max is proven to decline with aging, yet people of all ages have been able to improve their scores.On average, VO2 max tends to decline slowly in young adulthood at about 5% per decade, increasing to 10% per decade in middle age and about 15% per decade through the retirement years (1, 8, 9). Decreasing space for blood flow in the heart and blood vessels, smaller air sacs in the lungs, and less elasticity in the heart valves and lung tissue may explain this change in the body's performance over time (10).

This age-related decline seems to occur in people of all ability levels, from non-exercisers to fit and athletic people. The advantage for fit people who remain active is that their conditioning compares favorably with adults 20 or 30 years younger (1).

Studies show that with concentrated effort you can improve your low VO2 max, even later in life (11). There are even senior athletes who increased their aerobic capacity steadily over years of training. Our aging and exercise article features inspiring examples of people who seem to defy the odds and improve their fitness, even late in life.

Low VO2 max and nutrition

The typical Western diet is calorie-dense and nutrient-poor. 58% of calories consumed in the US are from ultra-processed foods, such as cookies, cakes, chips, soda, and processed meat (12).

By contrast, the Mediterranean Diet, which includes a high intake of fruits and vegetables, legumes, olive oil, grains, potatoes, and smaller portions of eggs, cheese, fish, and poultry, has long been associated with longevity and improved cardiovascular health.

A review of studies found that high adherence to the Mediterranean Diet is also associated with improved cardiovascular and overall physical fitness (13).

The Mediterranean diet, long associated with heart health, is also connected to improved cardiovascular fitness.

The Mediterranean diet, long associated with heart health, is also connected to improved cardiovascular fitness.Low VO2 Max and Stress

Stress can interfere with exercise training, but scientists verified that cardiovascular exercise can relieve stress-related symptoms.

Stress can interfere with exercise training, but scientists verified that cardiovascular exercise can relieve stress-related symptoms.The American Psychological Association reported that 34% of adults are overwhelmed by stress (Stress in America 2022). Symptoms include headache, fatigue, anxiety, depression, and difficulty sleeping.

Over 70% of adults experience negative impacts either on their eating habits, interests in hobbies or activities, or physical health. Though stress can interfere with our exercise training, even a single exercise session can reduce symptoms.

Developing a higher level of cardio fitness can even lower your reactivity to acute stressors (14, 15).

Chronic work or relational stressors can lead to increased blood pressure and higher risks of cardiovascular disease, such as arrhythmia, MI, and heart failure. Improving a low VO2 max through cardiovascular training is an effective way to control the risk of these conditions, though the untrained should start slowly for the first 6-8 weeks to lower their risk of an acute cardiac event (14, 15).

Low VO2 max and sleep quality

About 1/3 of US adults get less than 7 hours of sleep per night (16). A review of studies found that total or partial sleep deprivation, going to bed too late, or waking up early (without getting enough sleep) had a moderate detrimental impact on endurance performance (17).

In addition, lack of sleep has been shown to limit recovery after exercise and increase the risk of injury from exercise, all of which can worsen your results from training. Fortunately, given a sufficient time window for rest each night, consistent cardiovascular exercise can improve sleep quality just as it reduces symptoms of stress (18).

Lack of sleep reduces endurance performance, but regular exercise can improve sleep quality.

Lack of sleep reduces endurance performance, but regular exercise can improve sleep quality.Low VO2 max and genetics

Some people have better genetics for VO2 max, but even our genes can be enhanced by exercise training.

Some people have better genetics for VO2 max, but even our genes can be enhanced by exercise training.As we might expect to find with any human ability, studies have shown that low VO2 max and the trainability of cardio fitness may vary due to inherited ability and family environments. The Heritage Family Study observed significant differences in VO2 max in a diverse population of young and middle-aged males, all of whom had sedentary activity levels (19, 20).

They found up to a 50% difference in VO2 max when comparing the majority (2/3) of participants. Heritage estimated that 30% of this difference in untrained VO2 max comes from genetics, in agreement with other studies (21).

Heritage also found differences in response to training among their participants. While most of the men benefited significantly from endurance training, among the middle 2/3 there was a 70% difference in their improvement of VO2 max after exercise training. Heritage estimated that nearly 1/2 of the difference was due to genetics and family environment (20).

While some may have a natural advantage in VO2 max and trainability, even genetics can be affected by training, according to a 2008 study.

Telomeres are structures that protect the DNA code in cells, and healthy telomeres help prevent the aging process.The study found that regular leisure-time exercise helped maintain the proper length of telomeres in white blood cells (22).

Have cardio workouts been long and draining to you lately? Need to get back in shape and wondering how to make it happen? Find out how to overcome the hurdles of poor fitness in this new YouTube video from Why I Exercise.

Overcoming limiting factors to improve your low VO2 max

The factors that can limit your success in VO2 max training may be complex and multifaceted, but the solutions are often more straightforward. Establishing a doable training program you’ll look forward to practicing is central to your success at any age or condition.

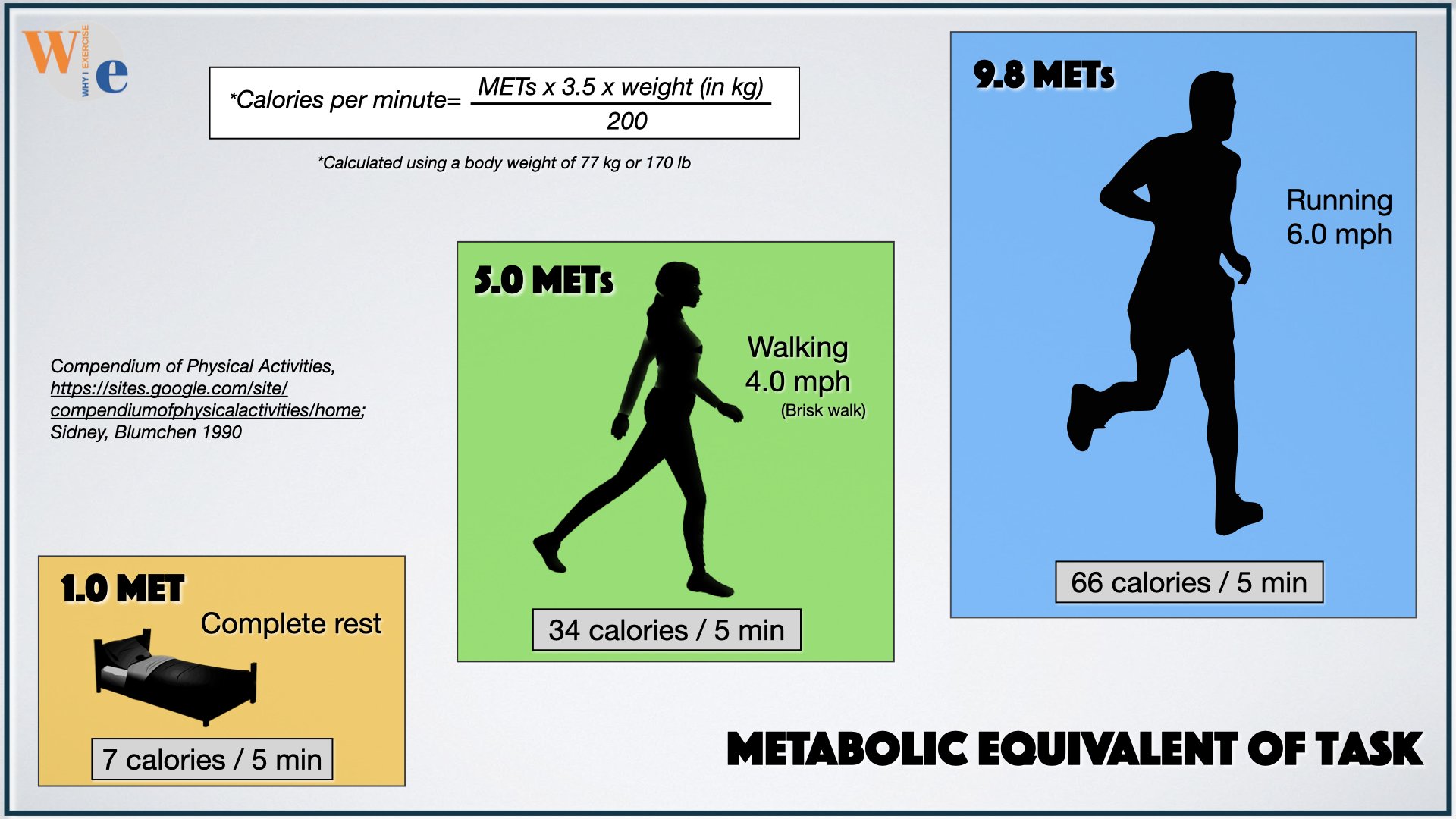

It doesn’t require conventional exercise to increase your energy and get health benefits. Our article on Metabolic Equivalent compares all kinds of physical activities, including sports, for their intensity and calories burned. I recommend picking activities that are doable and enjoyable so you’ll be able to stay active long term.

A modest amount of consistent exercise should help address factors associated with low VO2 max, such as stress and sleep quality. 12 minutes of consistent, moderate intensity exercise yields +2 years of life expectancy compared to not exercising.

Alternatively, people who take 5800+ steps per day have a 40% lower risk of death compared to non-exercisers. You can collect remarkable health benefits before you train enough to improve your VO2 max.

The next step? Gradually build (up to 10% increase per week) to 30-minute moderate training sessions, 3x per week. This amount of training is enough to improve your VO2 max, affect the age-related decline, and likely help with your body fat distribution.

If you haven’t tested yourself yet, our VO2 max article will help you pick your fitness test and find out where you stand! You’ll also learn the most effective methods for improving your cardio fitness.

Related Articles

Researchers found that the equivalent of a daily 11-minute walk made a two-year difference in life expectancy. Find out whether you’re getting enough exercise each week.

Which workouts can you count on when you need to improve your VO2 max? Compare steady-state moderate exercise to intervals, threshold, and sprint training to find the best ways to update your routine.

Cardio fitness, or VO2 max, is considered equal to vital signs such as heart rate and blood pressure. Test yourself and compare your score to research standards for 10-year survival!

References

1) Hemmingsson E, Väisänen D, et al., Combinations of BMI and cardiorespiratory fitness categories: trends between 1995 and 2020 and associations with CVD incidence and mortality and all-cause mortality in 471 216 adults. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022 May 6;29(6):959-967. doi: 10.1093/eurjpc/zwab169. PMID: 34669922.

2) Dagan SS, Segev S, et al., Waist circumference vs body mass index in association with cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy men and women: a cross sectional analysis of 403 subjects. Nutr J. 2013 Jan 15;12:12. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-12. PMID: 23317009; PMCID: PMC3564926.

3) Armour BS, Courtney-Long E, et al., Estimating disability prevalence among adults by body mass index: 2003-2009 National Health Interview Survey. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E178; quiz E178. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.120136. PMID: 23270667; PMCID: PMC3534133.

4) Stone AA, Broderick JE. Obesity and pain are associated in the United States. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012 Jul;20(7):1491-5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.397. Epub 2012 Jan 19. Erratum in: Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012 Jul;20(7):1546. PMID: 22262163.

5) Barry VW, Caputo JL, et al,. The Joint Association of Fitness and Fatness on Cardiovascular Disease Mortality: A Meta-Analysis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2018 Jul-Aug;61(2):136-141. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2018.07.004. Epub 2018 Jul 5. PMID: 29981352.

6) Ricketts TA, Sui X, et al, Addition of Cardiorespiratory Fitness Within an Obesity Risk Classification Model Identifies Men at Increased Risk of All-Cause Mortality. Am J Med. 2016 May;129(5):536.e13-20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.11.015. Epub 2015 Nov 28. PMID: 26642906.

7) Ortega FB, Lee DC, et al., The intriguing metabolically healthy but obese phenotype: cardiovascular prognosis and role of fitness. Eur Heart J. 2013 Feb;34(5):389-97. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs174. Epub 2012 Sep 4. PMID: 22947612; PMCID: PMC3561613.

8) Jackson AS, Sui X, et al, Role of lifestyle and aging on the longitudinal change in cardiorespiratory fitness. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Oct 26;169(19):1781-7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.312. PMID: 19858436; PMCID: PMC3379873.

9) Fleg JL, Morrell CH, et al, Accelerated longitudinal decline of aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. Circulation. 2005 Aug 2;112(5):674-82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.545459. Epub 2005 Jul 25. PMID: 16043637.

10) Jakovljevic, DG. Physical activity and cardiovascular aging: Physiological and molecular insights, Experimental Gerontology, Volume 109, 2018, Pages 67-74, ISSN 0531-5565, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.05.016.

11) Sian, T.S., Inns, T.B., Gates, A. et al. Equipment-free, unsupervised high intensity interval training elicits significant improvements in the physiological resilience of older adults. BMC Geriatr 22, 529 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03208-y

12) Martínez Steele E, Baraldi LG, et al., Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016 Mar 9;6(3):e009892. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009892. PMID: 26962035; PMCID: PMC4785287.

13) Bizzozero-Peroni B, Brazo-Sayavera J, et al High Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet is Associated with Higher Physical Fitness in Adults: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr. 2022 Dec 22;13(6):2195-2206. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmac104. PMID: 36166848; PMCID: PMC9776663.

14) Schilling R, Herrmann C, Ludyga S, Colledge F, Brand S, Pühse U, Gerber M. Does Cardiorespiratory Fitness Buffer Stress Reactivity and Stress Recovery in Police Officers? A Real-Life Study. Front Psychiatry. 2020 Jun 23;11:594. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00594. PMID: 32670116; PMCID: PMC7331850.

15) Franklin BA, Rusia A, Haskin-Popp C, Tawney A. Chronic Stress, Exercise and Cardiovascular Disease: Placing the Benefits and Risks of Physical Activity into Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Sep 21;18(18):9922. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189922. PMID: 34574843; PMCID: PMC8471640.

16) Pankowska MM, Lu H, et al. Prevalence and Geographic Patterns of Self-Reported Short Sleep Duration Among US Adults, 2020. Prev Chronic Dis 2023;20:220400. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd20.220400

17) Craven J, McCartney D, et al Effects of Acute Sleep Loss on Physical Performance: A Systematic and Meta-Analytical Review. Sports Med. 2022 Nov;52(11):2669-2690. doi: 10.1007/s40279-022-01706-y. Epub 2022 Jun 16. PMID: 35708888; PMCID: PMC9584849.

18) Osailan AM, Elnaggar RK, et al., The Association between Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Reported Physical Activity with Sleep Quality in Apparently Healthy Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Apr 17;18(8):4263. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084263. PMID: 33920540; PMCID: PMC8072608.

19) BOUCHARD, CLAUDE; DAW, E. WARWICK,et al. Familial resemblance for VO2 max in the sedentary state: the HERITAGE family study. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 30(2):p 252-258, February 1998.

20) Marie Klevjer, Ada N Nordeidet, Anja Bye,The genetic basis of exercise and cardiorespiratory fitness – relation to cardiovascular disease, Current Opinion in Physiology, Volume 33, 2023,100649, SSN 2468-8673, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cophys.2023.100649.

21) SARZYNSKI, MARK A.; RICE, TREVA K et al., The HERITAGE Family Study: A Review of the Effects of Exercise Training on Cardiometabolic Health, with Insights into Molecular Transducers. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 54(5S):p S1-S43, May 2022. | DOI: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002859

22) The Association Between Physical Activity in Leisure Time and Leukocyte Telomere Length 2008, Lynn F. Cherkas, PhD; Janice L. Hunkin, BSc; Bernet S. Kato, PhD; J. Brent Richards, MD;